Making a difference for those with learning differences

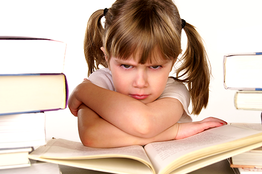

Does this picture make you sad, angry, or frustrated? Reading with your kids is supposed to be fun, right?  But what happens when it’s become a battle, with tears or angry standoffs?  Maybe you loved to read as a child yourself, and can’t understand why it’s so hard for your child? If you’ve reached the point where your child gets stressed about reading, or point-blank refuses to read at all, here are some things that can help:

Read signs aloud. Eg. “Great – we’re just in time. Look, the sign says OPEN.” Or “Uh oh – that sign says No Dogs. We’ll have to leave Scruffy in the car and just make it a short walk.”

Show them how reading can be fun. Eg. React out loud when you read something funny (on your phone, perhaps) and then share the joke with them, pointing out the words that make it funny.

2. Read a simple story to them, then act it out together (Eg. Little Red Riding Hood, Where the Wild Things Are, The Gruffalo). 3. Make books to record family events (birthdays, holidays) including photos. Keep captions very short and simple. Eg. My 8th Birthday. Mum gave me a ball.  Dad gave me some shoes. Grandad gave me a shirt. I am ready to play football. Make reading a fun part of everyday life.

2 Comments

Craig and Michelle were delighted by the birth of their first child, Jackson. When little Sophie arrived just after Jackson’s second birthday, their family was complete. Jackson was still a little unsteady on his feet when Sophie started crawling. He’d been a late walker, but Craig and Michelle weren’t overly concerned; Craig’s mother said he’d been much the same.  After the “Obesity Epidemic” in the early years of the century the government of New Realand had decided to put a greater emphasis on basic fitness. Running and jumping, in particular, were seen as necessary skills in establishing the nation’s place in relation to the fitness levels in other OECD countries. Now, in 2045, society had undergone a major shift and everyone valued running and jumping skills. Indeed, many people in the small city of Marathon had occupations supporting related industries such as sports shoe manufacture, physiotherapy and running fashions. Running to work was encouraged (this had also reduced carbon emissions considerably) and most employers provided treadmills in their staff tearooms. Every day Michelle ran the three kilometres to work after dropping Sophie at daycare. Already little Sophie was begging her mother to stop the stroller at the end of the street so they could run the last few metres to the centre together. Craig had always found running more difficult. He’d gone to extra exercise classes as a child, but he just seemed to have weak leg muscles and nothing much helped. Lately he had taken to riding a small pavement scooter to his job at the bank. There had been a few derogatory comments at first, but at least it meant he didn’t have to spend the rest of the day in pain – and he could get to work on time. Young Jackson had started school. He was already learning to read and showed natural leadership ability. However, his legs were still not strong. As Craig watched his young son stumble in the door after trying to run home like the other children, he recognised his own pain being reflected in his son. Despite his lack of running skill, or perhaps because of it, Jackson’s upper body developed considerable strength. Craig and Michelle arranged for him to have swimming lessons, in the hope that his legs would also be strengthened. It wasn’t long before Jackson joined the swimming club and started achieving recognition for his ability. A row of certificates soon adorned the fridge. It didn’t seem to matter that his legs were not becoming stronger; Jackson’s confidence grew with his success. Soon after Jackson’s sixth birthday Craig and Michelle were asked to meet his teacher to discuss recent test results. Apparently Jackson was achieving much lower than his peers in running and jumping skills. Craig pointed out that Jackson was doing very well with other things, like reading and swimming. The teacher reminded him of the Government’s policy that “all children should be able to run and jump successfully by age nine”. If Jackson were to get anywhere near that standard he would have to go into the school’s Running Recovery Programme. That would mean 30 minutes of intensive running training with a tutor every day. Real gains would only be made if Michelle followed up at home with leg strengthening exercises and more running for at least 10 to 15 minutes each night. Jackson felt a sense of relief when he finished primary school and its succession of remedial running programmes. He had continued with swimming, taken up archery and won the speech competition for the past two years. He liked nothing more than to lie on the couch and devour a good book. Unfortunately, Jackson found that nearly every high school subject depended on running in some way. Even in English they were expected to run to class, run to get their books and run to the library. They wrote essays about great runners. The Remedial Running teacher at the high school suggested that Craig and Michelle take Jackson for a Physical Assessment to determine just what the problem was. They felt they were already well aware of their son’s difficulties, but decided to go ahead with the assessment. The results were very interesting. They recommended that leg braces, or even a wheelchair, be provided for Jackson when races were held. Jackson was reluctant to look different from his peers, but agreed to trial the wheelchair for the next running test. As soon as he tried it his upper body strength was apparent; he finished the race near the front of his class. His friends congratulated him, but others made comments about ‘unfair advantage’. They all admitted that he must have incredible arm strength to operate the chair. The emphasis on running meant that their arms were not nearly as strong as their legs. Jackson began to realise that some other students wore leg braces for the running races, and a girl in Year 11 used a wheelchair. Shortly after the beginning of the next school year Jackson arrived home one day, threw his bag on the floor and went straight to his room. Craig and Michelle eventually got the whole story from him. All of the school students were sitting the annual Running Achievement Tests. Jackson had expected to be allowed to use his chair, as he did for other running tests. The teacher had said he couldn’t, as this was a standardised test and they wanted to see how well everyone could perform with no assistance.  “But I can’t run at all,” Jackson had protested. “Yes, well, we know that, but we just want to see how bad at it you really are. Umm… I mean… just do your best, Jackson. That’s all we ask.” Sure enough, the results showed that Jackson couldn’t run. In fact, he was the poorest in his class at running. “Now tell us something we don’t know,” thought Craig and Michelle as they read their son’s Progress Report. Each year Craig and Michelle listened as another group of teachers expressed their concerns at Jackson’s Running Achievement Test results. Each year they insisted that the RATs were not a true reflection of their son’s capabilities. It wasn’t until Jackson reached the senior level that he had a chance to specialise in subjects that reflected his ability. He particularly enjoyed English at this level, as it no longer included much running. His real passion, however, was swimming. He even coached a junior swim squad as part of his community service requirement. As Jackson hobbled onto the stage at his final school prizegiving Craig and Michelle beamed and applauded enthusiastically as he was handed an armful of trophies and certificates for his achievements.  The parents of the Running Dux, sitting two rows behind, were heard to mutter: “What’s the use of all that if you can’t even run!” Copyright G Knopp 2007

or, why some people with dyslexia struggle to find the right word. Have you ever noticed that some people mix up words when they’re talking? They may mispronounce the word, or say a word that sounds similar to the right one, or they may ummm and aaahhh as they try to remember the word they need. This is an issue with word retrieval – having the right word on the tip of your tongue. Sometimes it’s called speed of lexical access – how quickly you can come up with the word you need. They use this same approach when looking at words. Some words easily give a mental picture, but many don’t. It’s easier to picture ‘elephant’ than ‘was’, and many people with dyslexia find it easier to read the word ‘elephant’ than the word ‘was’! A mother told me about her eight-year-old daughter reading a book and coming to the word ‘jacket’, which she read as ‘warm coat’. This is likely to be because she was picturing the meaning of the word in her mind, and that was more important to her than the actual letters in the word. As people with dyslexia are often creative and imaginative, they may group information differently in their minds. When asked to find the things that go together out of this group of pictures they may choose boat and feather, because they can both sit on water, but a word-thinker may choose boat, coat and goat, because the words sound alike. A teenager was repeating a story she had just heard. As she came to the words ‘station wagon’ she clasped her hands to her cheeks, said “Oh no!” and then said ‘wation stagon’. She then groaned and said “Oh. It’s happened again!” A mother was chatting to me about her son’s school work. She remarked: "Well, he is making process, but it's slow process." Yes, dyslexia does tend to run in families.

(Note: Rapid Naming is not a test for dyslexia – it is used as a small part of the process of finding out whether someone has a specific learning difficulty).  Another thing I’ve noticed in my work as an assessor is that many people with dyslexia have very good listening comprehension – they have no problem understanding what people are saying. Many find it harder to put their thoughts into words, so their oral expression score may be lower. Of course, it is usually even harder to put their thoughts into writing.

This problem can lead to frustration, embarrassment and humiliation for the person. They often become very quiet, as it’s easier not to speak much at all. So, what can be done about problems with word retrieval? |

| But what if people who don’t have such issues, those like me who are good spellers, who can speak and read clearly and fluently, learnt to value those who have problems with words, but are creative, imaginative, out-of-the-box thinkers and valued them just as they are? It’s no coincidence that many artists, inventors, designers, musicians, mechanics, pilots, entrepreneurs etc. are dyslexic. The world needs those with dyslexia. |

Write something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview.

November 2021

June 2017

April 2017

Clarity Dyslexia Solutions |

17 Oakden Drive

Darfield 7510, Canterbury, New Zealand |